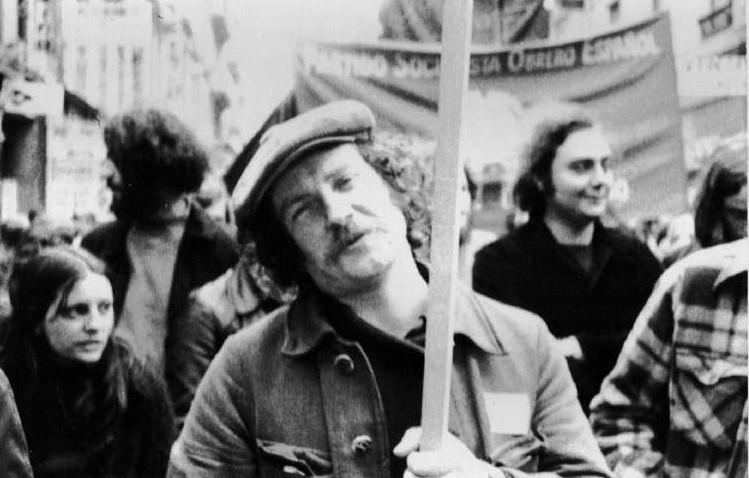

Daniel Colson (1943-2026)

Freedom News - Sunday, January 11, 2026

A singular and generous thinker of anarchism, his work traced living lines of revolt and creation

~ David Berry ~

Daniel Colson, anarchist theorist and labour historian, died on 9 January in Lyon. He was 82.

Colson was an active member of the anarchist movement in Lyon from the early 1970s, a member of the collective that ran the city’s anarchist bookshop ‘La Gryffe’ from its creation in 1978, and a member of the editorial collective that has produced the anarchist review Réfractions since 1997. A professor of sociology at the University of Saint-Etienne, he published extensively on labour history, revolutionary syndicalism, anarchism and, latterly, philosophy.

Colson first moved to Lyon, France’s second biggest city, in 1966, when he went to university there to study sociology, after two years studying philosophy at a seminary near Clermont-Ferrand. At the university he discovered revolutionary politics, and soon became active in the student movement, which was dominated in the late 1960s by Maoists, Trotskyists and other assorted ‘gauchistes’ (‘leftists’—originally a pejorative term used of the student revolutionaries of 1968 by the French Communist Party, referencing Lenin’s “Left-Wing” Communism, An Infantile Disorder).

Through his friendship with the libertarian communist Michel Marsella, Colson also learned about anarchism, the Socialism or Barbarism group around Cornelius Castoriadis, Situationism, Luxemburgism, etc. Like so many of his contemporaries he was involved in the campaign against US imperialism and in particular the Vietnam war, and was the prime mover in the ‘Vietnam Committee’ in Lyon’s old town. The group produced a newsletter, Informations rassemblées à Lyon (IRL), and after the repression and collapse of the 1968 movement, the Vietnam Committee transformed itself into the ‘Comité de quartier du Vieux-Lyon’ (Old Lyon Neighbourhood Committee).

When asked years later what the objectives of this committee had been, Colson replied: “Nothing less than creating the embryo of an insurrection at a local level.” Influenced by the automobile workers occupying the local Berliet factories, the group decided to occupy the local ‘Maison des jeunes’ (youth centre), which had been where the committee had met over the previous months. “We were very ambitious. We were seriously hoping, when the right conditions arose, to take over the local police station—including its armoury.” That plan never materialised, although the group did occupy the town hall briefly.

Colson was inspired by 1968 and especially by his experience of “spontaneity in action and in organisation”, including widespread co-operation between students and workers. He was also inspired by the discovery of three important books: the four-volume history of the First International written by the Swiss anarchist James Guillaume; the Russian anarchist Voline’s The Unknown Revolution (originally published in French in 1947, but republished in the aftermath of 1968 in a series edited by Daniel Guérin and the anarchist artist Jean-Jacques Lebel); and Anti-Œdipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972) by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari.

Not that he understood Anti-Œdipus at all when he first tried to read it—he found it “pretty indigestible” in fact— and even ten years later when he tried again, it was only the first chapter that he really got to grips with: for Colson, that chapter successfully demolished the “enormous Marxist theoretical apparatus” that dominated the French left at that time, and made clear “not only the theoretical but also the emancipatory, ethical, philosophical and practical power of anarchism”.

Colson was actively involved with a number of anarchist newspapers: the Cahiers de mai (the May Notebooks, which was launched in June 1968 and was the voice of the Action Committees which had sprung up across France), ICO (Informations et Correspondences Ouvrières, Workers’ News and Letters, focussed on autonomous workers’ struggles, outside of trade unions and parties), and IRL (Informations rassemblées à Lyon, literally News Gathered in Lyon, which published eye-witness accounts and documents on social struggles in the Lyon area not published by the mainstream press or the main left-wing papers). IRL, which Colson helped create, was interested in workers’ struggles, but also illegalism and other forms of resistance, and discussed a range of movements: anarchism, council communism, feminism, ecology, antimilitarism, sexual liberation, etc.

In 1978, Colson was one of the original group of anarchist activists who set up the La Gryffe bookshop in Lyon, and the collective is still going strong. As well as selling the usual range of anticapitalist, antiauthoritarian material, La Gryffe also has a meeting room that regularly hosts debates, exhibitions, film showings, etc. When Colson published a book about the collective in 2020, he was careful not to give an idealised view of a successful anarchist collective at work, but to highlight also the long and sometimes difficult history that La Gryffe was built on, including some serious differences of opinion and conflicts within the collective, but conflicts which were worked through and resolved according to anarchist principles.

Having returned to academia, Colson gained his doctorate in 1983 with a thesis—later published as a book—on anarcho-syndicalism and communism in the labour movement in Saint-Etienne, 1920-25. (If ever you’ve been confused about the difference between the terms ‘syndicalism’, ‘revolutionary syndicalism’ and ‘anarcho-syndicalism’, and how the once revolutionary syndicalist French labour movement came to be dominated by Communism, this is the book for you.) A second historical-sociological book followed in 1998 on the iron and steel industry—and its owners, the famous ‘iron barons’ or forgemasters—in Saint-Etienne from the mid-nineteenth century to the First World War.

Colson explained once in a talk he gave on ‘Proudhon and the contemporary relevance of anarchism’—the main thrust of which was to argue for the rehabilitation of Proudhon, who remained unpopular in anarchist circles—that he had discovered Proudhon at about the same time in the 1970s that he discovered “the left-wing Nietzscheanism” of Foucault and especially Deleuze. Deleuze, he argued, “developed an emancipatory thought which had a lot in common with Proudhon.”

Indeed, moving away from his earlier sociological work, and after writing books on Proudhon and Malatesta, Colson became increasingly focussed on philosophy, and was especially interested in Spinoza, Leibniz, Nietzsche, Deleuze and Guattari (among others) and how their thinking related to anarchism. This led to a number of conference papers, journal articles and books on these subjects—in 2022, for instance, he published a book on ‘working-class anarchism and philosophy’. Unfortunately only one of his books has been translated (by Jesse Cohen) into English: the Little Philosophical Lexicon of Anarchism. From Proudhon to Deleuze—“a provocative exploration of hidden affinities and genealogies in anarchist thought”.

Daniel Colson was an active member of the anarchist movement in Lyon from the early 1970s, a member of the collective that ran the city’s anarchist bookshop ‘La Gryffe’ from its creation in 1978, and a member of the editorial collective that has produced the anarchist review Réfractions since 1997. A professor of sociology at the University of Saint-Etienne, he published extensively on labour history, revolutionary syndicalism, anarchism and, latterly, philosophy.

Colson first moved to Lyon, France’s second biggest city, in 1966, when he went to university there to study sociology, after two years studying philosophy at a seminary near Clermont-Ferrand. At the university he discovered revolutionary politics, and soon became active in the student movement, which was dominated in the late 1960s by Maoists, Trotskyists and other assorted ‘gauchistes’ (‘leftists’—originally a pejorative term used of the student revolutionaries of 1968 by the French Communist Party, referencing Lenin’s “Left-Wing” Communism, An Infantile Disorder). Through his friendship with the libertarian communist Michel Marsella, Colson also learned about anarchism, the Socialism or Barbarism group around Cornelius Castoriadis, Situationism, Luxemburgism, etc.

Like so many of his contemporaries he was involved in the campaign against US imperialism and in particular the Vietnam war, and was the prime mover in the ‘Vietnam Committee’ in Lyon’s old town. The group produced a newsletter, Informations rassemblées à Lyon (IRL), and after the repression and collapse of the 1968 movement, the Vietnam Committee transformed itself into the ‘Comité de quartier du Vieux-Lyon’ (Old Lyon Neighbourhood Committee).

When asked years later what the objectives of this committee had been, Colson replied: “Nothing less than creating the embryo of an insurrection at a local level.” Influenced by the automobile workers occupying the local Berliet factories, the group decided to occupy the local ‘Maison des jeunes’ (youth centre), which had been where the committee had met over the previous months. “We were very ambitious. We were seriously hoping, when the right conditions arose, to take over the local police station—including its armoury.” That plan never materialised, although the group did occupy the town hall briefly.

Colson was inspired by 1968 and especially by his experience of “spontaneity in action and in organisation”, including widespread co-operation between students and workers. He was also inspired by the discovery of three important books: the four-volume history of the First International written by the Swiss anarchist James Guillaume; the Russian anarchist Voline’s The Unknown Revolution (originally published in French in 1947, but republished in the aftermath of 1968 in a series edited by Daniel Guérin and the anarchist artist Jean-Jacques Lebel); and Anti-Œdipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972) by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. Not that he understood Anti-Œdipus at all when he first tried to read it—he found it “pretty indigestible” in fact— and even ten years later when he tried again, it was only the first chapter that he really got to grips with: for Colson, that chapter successfully demolished the “enormous Marxist theoretical apparatus” that dominated the French left at that time, and made clear “not only the theoretical but also the emancipatory, ethical, philosophical and practical power of anarchism”.

![]()

Colson was actively involved with a number of anarchist newspapers: the Cahiers de mai (the May Notebooks, which was launched in June 1968 and was the voice of the Action Committees which had sprung up across France), ICO (Informations et Correspondences Ouvrières, Workers’ News and Letters, focussed on autonomous workers’ struggles, outside of trade unions and parties), and IRL (Informations rassemblées à Lyon, literally News Gathered in Lyon, which published eye-witness accounts and documents on social struggles in the Lyon area not published by the mainstream press or the main left-wing papers). IRL, which Colson helped create, was interested in workers’ struggles, but also illegalism and other forms of resistance, and discussed a range of movements: anarchism, council communism, feminism, ecology, antimilitarism, sexual liberation, etc.

In 1978, Colson was one of the original group of anarchist activists who set up the La Gryffe bookshop in Lyon, and the collective is still going strong. As well as selling the usual range of anticapitalist, anti-authoritarian material, La Gryffe also has a meeting room that regularly hosts debates, exhibitions, film showings, etc. When Colson published a book about the collective in 2020, he was careful not to give an idealised view of a successful anarchist collective at work, but to highlight also the long and sometimes difficult history that La Gryffe was built on, including some serious differences of opinion and conflicts within the collective, but conflicts which were worked through and resolved according to anarchist principles.

Having returned to academia, Colson gained his doctorate in 1983 with a thesis—later published as a book—on anarcho-syndicalism and communism in the labour movement in Saint-Etienne, 1920-25. (If ever you’ve been confused about the difference between the terms ‘syndicalism’, ‘revolutionary syndicalism’ and ‘anarcho-syndicalism’, and how the once revolutionary syndicalist French labour movement came to be dominated by Communism, this is the book for you.) A second historical-sociological book followed in 1998 on the iron and steel industry—and its owners, the famous ‘iron barons’ or forge-masters—in Saint-Etienne from the mid-nineteenth century to the First World War.

Colson explained once in a talk he gave on ‘Proudhon and the contemporary relevance of anarchism’—the main thrust of which was to argue for the rehabilitation of Proudhon, who remained unpopular in anarchist circles—that he had discovered Proudhon at about the same time in the 1970s that he discovered “the left-wing Nietzscheanism” of Foucault and especially Deleuze. Deleuze, he argued, “developed an emancipatory thought which had a lot in common with Proudhon.” Indeed, moving away from his earlier sociological work, and after writing books on Proudhon and Malatesta, Colson became increasingly focussed on philosophy, and was especially interested in Spinoza, Leibniz, Nietzsche, Deleuze and Guattari (among others) and how their thinking related to anarchism. This led to a number of conference papers, journal articles and books on these subjects—in 2022, for instance, he published a book on ‘working-class anarchism and philosophy’. Unfortunately only one of his books has been translated (by Jesse Cohen) into English: the Little Philosophical Lexicon of Anarchism. From Proudhon to Deleuze—“a provocative exploration of hidden affinities and genealogies in anarchist thought”.

The post Daniel Colson (1943-2026) appeared first on Freedom News.